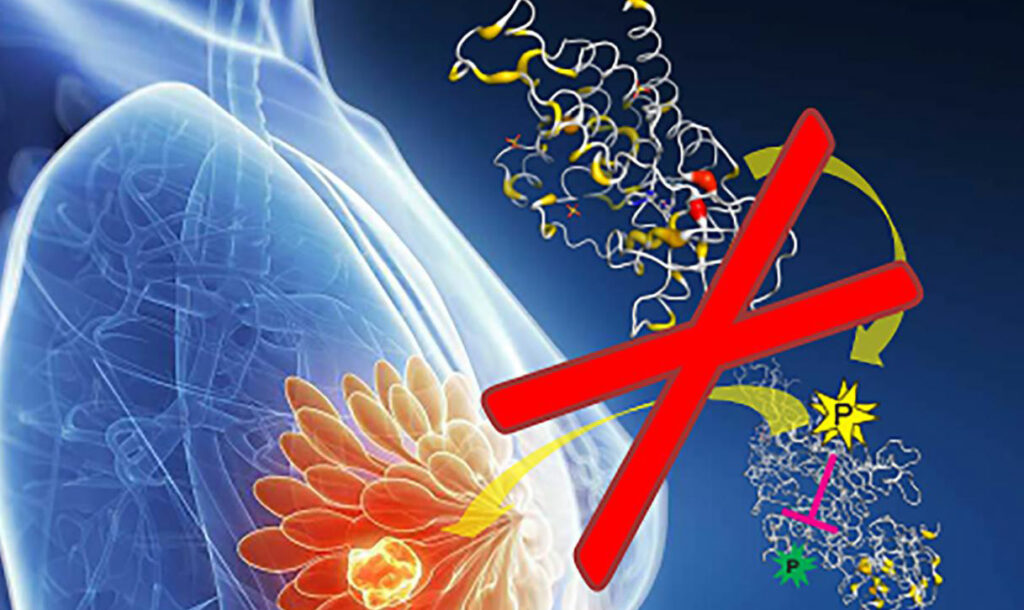

Researchers discovered that cancers wrap themselves in an invisible protective shield. and they learned that they could break into that shield with the right drugs. When the immune system is free to attack, cancers can shrink and stop growing or even disappear in lucky patients with the best responses.

As reported in IE on October 16, 2013 – AN EXPERIMENTAL IMMUNOTHERAPY COULD HELP T-CELLS, A TYPE OF WHITE BLOOD CELL, RECOGNIZE AND DESTROY CANCER CELLS.

For more than a century, researchers were puzzled by the uncanny ability of cancer cells to evade the immune system. They knew cancer cells were grotesquely abnormal and should be killed by white blood cells. In the laboratory, in Petri dishes, white blood cells could go on the attack against cancer cells. Why, then, could cancers survive in the body ?

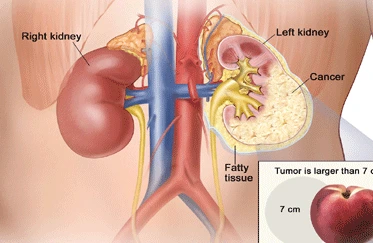

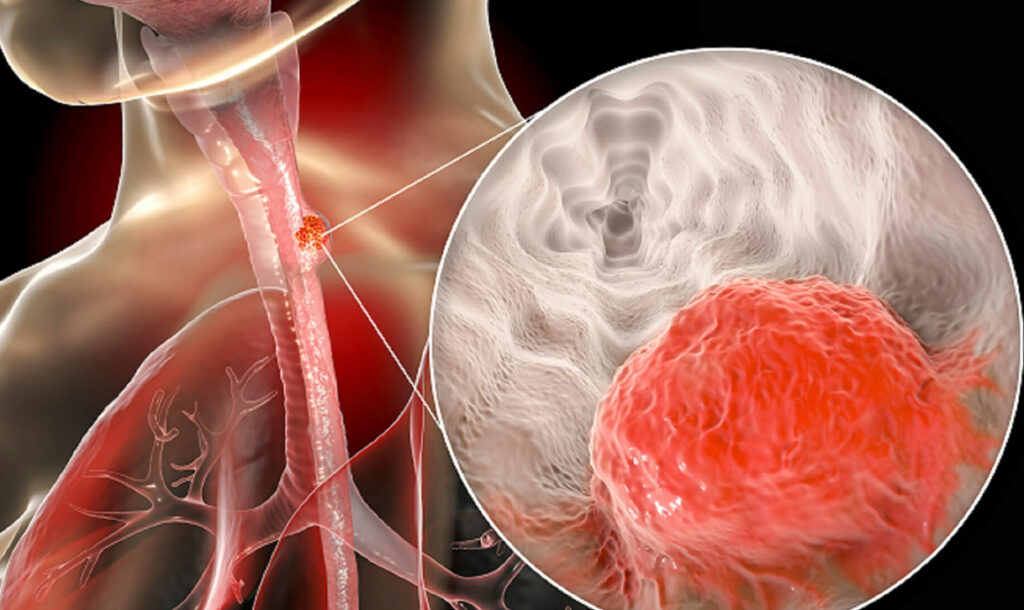

The answer, when it finally came in recent years, arrived with a bonus: a way to thwart a cancer’s strategy. Researchers discovered that cancers wrap themselves in an invisible protective shield. and they learned that they could break into that shield with the right drugs. When the immune system is free to attack, cancers can shrink and stop growing or even disappear in lucky patients with the best responses. It may not matter which type of cancer a person has. What matters is letting the immune system do its job. So far, the drugs have been tested and found to help patients with melanoma, kidney and lung cancer. In preliminary studies, they also appear to be effective in breast cancer, ovarian cancer and cakncers of the colon, stomach, head and neck, but not the prostate.

It is still early, of course, and questions remain. Why do only some patients respond to the new immunotherapies ? Can these responses be predicted ? Once beaten back by the immune system, how long do cancers remain at bay ? Still, researchers think they are seeing the start of a new era in cancer medicine.

“Amazing,” said Dr Drew Pardoll, the immunotherapy research director at John Hopkins School of Medicine. This period will be viewed as an inflection point, he said, a moment in medical history when everything changed.

“A game-changer,” said Dr Renier J Brentjens, a leukemia specialist at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre. “A watershed moment,” said his colleague, Dr Michel Sadelain. (Both say they have nofinancial interests in the new drugs; Dr Pardoll says he holds patents involving some immunotherapy drugs, but not the ones mentioned in this article.)

Researchers and companies say they are only beginning to explore the new immunotherapies and develop others to attack cancers, like prostate, that seem to use different molecules to evade immune attacks. They are at the earliest stages of combining immunotherapies with other treatments in a bid to improve results.

“I want to be very careful that we dot not overhype and raise patients’ epectations so high that we can never meet them,” said dr Alise reicin, a vice president at Merck for research and development. But the companies have an incentive to speed development of the drugs. They are expected to be expensive, and the demand huge. Delays even a few months mean a huge loss of potential income. Nils Lonberg, a senior vice president at bristol-Myers Squibb, notes that immunotherapy carries a huge advantage over drugs that attack mutated genes. The latter approach all but invites the cancer to escape, in the same way bacetria develop resistance to antibiotics. By contrast, immunotherapy drugs are simply encouraging the immune system to do what it is meant to do; it is not going to adapt to evade the drugs. “We are hoping to set up a fair fight between the immune system and the cancer,” Dr Lonberg said.