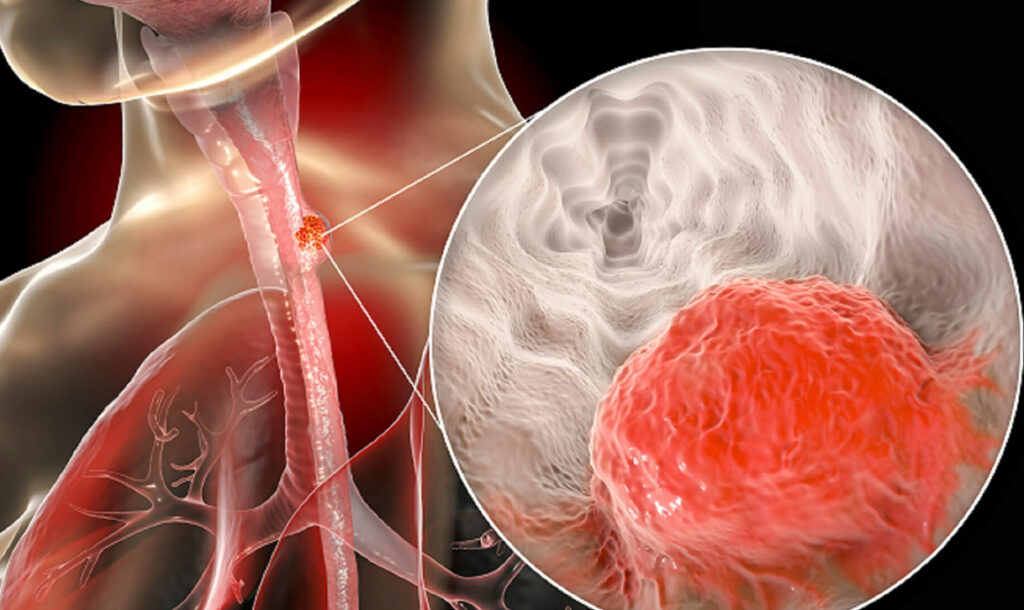

A little squeeze may be all that it takes to prevent malignant breast cells triggering cancer, research has shown.

A little squeeze may be all that it takes to prevent malignant breast cells triggering cancer, research has shown.

Laboratory experiments showed that applying physical pressure to the cells guided them back to a normal growth pattern.

Scientists believe the research provides clues that could lead to new treatments.

‘People have known for centuries that physical force can influence our bodies,’ said Gautham Venugopalan, a leading member of the research team at the University of California in Berkeley, US.Â

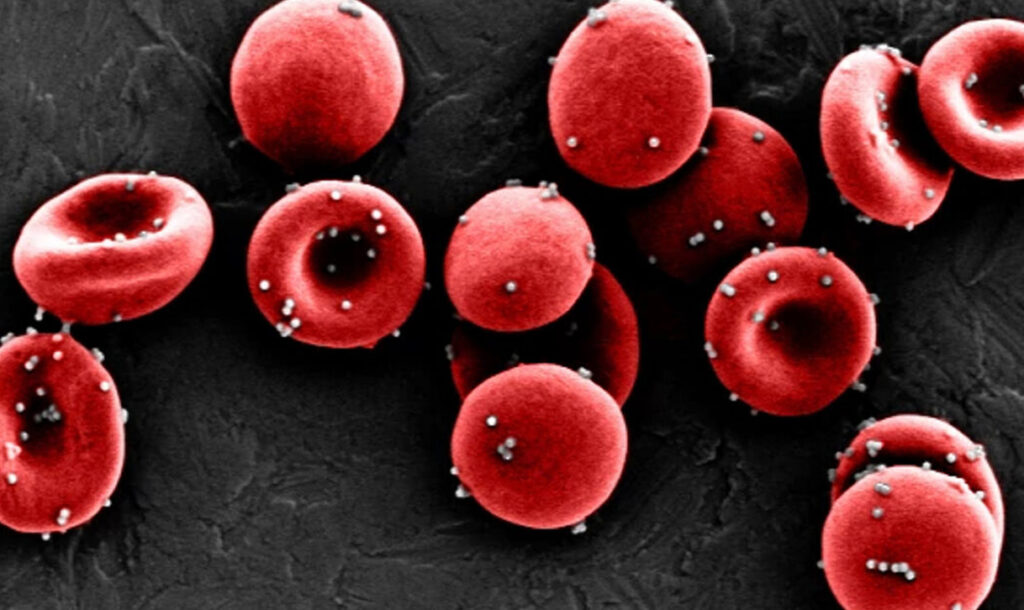

‘When we lift weights our muscles get bigger. The force of gravity is essential to keeping our bones strong. Here we show that physical force can play a role in the growth – and reversion – of cancer cells.’ The study involved growing malignant breast epithelial cells within a gel injected into flexible silicone chambers. This allowed the scientists to apply compression during the first stages of cell growth, effectively squashing the cells. Over time, the squeezed malignant cells began to grow in a more normal and organised way.

Once the breast tissue structure was formed the cells stopped growing, even when the compressive force was removed. Non-compressed cells continued to display the haphazard and uncontrolled growth that leads to cancer. ‘Malignant cells have not completely forgotten how to be healthy; they just need the right cues to guide them back to a healthy growth pattern,’ said Mr Venugopalan, a doctoral student. The results were presented today at the annual meeting of the American Society for Cell Biology in San Francisco.

Professor Daniel Fletcher, who runs the Berkeley laboratory, said: ‘We are showing that tissue organisation is sensitive to mechanical inputs from the environment at the beginning stages of growth and development. ‘An early signal, in the form of compression, appears to get these malignant cells back on the right track.’ However, the team do not envisage fighting breast cancer with a new range of compression bras.

Prof Fletcher said: ‘Compression, in and of itself, is not likely to be a therapy. But this does give us new clues to track down the molecules and structures that could eventually be targeted for therapies.’ Adding a drug that helps to prevent cells adhering to their neighbours reversed the effects of compression, the scientists found. The cells returned to a disorganised, cancerous state despite being compressed.